The M14 is one of the all-time great battle rifles of the 20th century. Though it only saw limited combat use in Vietnam, it proved to be a rifle to contend with and still sees service for ceremonial and other specialty uses. Sired to replace four weapons—the M1 Garand, the M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), the M1 Carbine and the M3 Grease Gun—the M14 was the U.S. military’s answer to new intermediate-caliber rifles that resulted from World War II. The Army saw the need for a select-fire battle rifle using high-capacity detachable box magazines, incorporating the capabilities of the M1 Garand as well as the automatic fire capabilities of the BAR in one weapon, to meet the needs of the growing threat of the Cold War.

Introduced in 1949, the Russian AK-47 made the M1 Garand obsolete in terms of firepower and maneuverability; pitched, close-quarter battles on forgotten hills during the Korean War were a painful lesson in the common foot soldier’s need for the firepower of a submachine gun without sacrificing the accuracy or terminal ballistics of a battle rifle.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Still Fighting

For its time, the M1 Garand was definitely ahead of the power curve. It brought higher capacity, a faster rate of fire and quicker reloads than the established bolt-action infantry rifles of the day. And it did this without sacrificing accuracy or lethality. Even today, the M1 is held in very high regard, with NRA matches specifically ruled around the original form of this legendary rifle.

“Even with less-than-optimal ammunition, the rifle is still capable of Sub-2-Moa Groups, which is the USMC’s standard for the M39 Emr.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The M14 was the result of budget-minded bean counters trying to keep the Army and politicians happy. What was created was simply an improved M1 Garand, with the minimal re-tooling of current factories and the ease with which the new 7.62mm NATO cartridge could be retrofitted to current M1s. After a long and stringent test phase, the M14 won out over a Fabrique Nationale (FN) candidate for the U.S. military’s new battle rifle.

Fast-forward half a century and you know that the AR “black gun” has completely taken over the tactical rifle market. However, the M14 (and the civilian M1A) still holds on. I remember my first encounter with this rifle when I was going through Small Arms Repairer (MOS 2111) training at Aberdeen Proving Grounds, Maryland, during the winter of 2003 and 2004. I was a young Marine, fresh out of boot camp, getting ready to execute orders for duty with the 3rd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment at Camp Lejeune. We were receiving our Special Weapons familiarization class when the instructor brought out the M14 designated marksman’s rifle (DMR). It was love at first sight. The sergeant explained that we, as pathetic excuses for armorers, where not allowed to conduct maintenance on this particular weapon, and that right was held only by the esteemed Precision Weapons Technicians (MOS 2112). Right then and there, I decided that I would become a “12” no matter what it took.

During my first combat deployment, I was a part of Combined Joint Task Force 76 (CJTF-76) stationed in Afghanistan for most of 2004. Well, my unit was there for most of it—I was medevac’d due to injuries sustained from a UH-60 Black Hawk crash in Khost Province. We had been supporting the 82nd Airborne with counterinsurgency operations, and many of the paratroopers carried rack-grade M14s with 4X ACOGs as a sort of DMR. Even to this day, I am a firm believer that the M14 was the perfect weapon for that terrain and envied the soldiers who had peace of mind concerning their tools.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

A Better Fighter

Enter Sage International and the U.S. Marine Corps M39 enhanced marksman rifle (EMR) project. The M39 was a groundbreaking undertaking in the Marine Corps for several important reasons. These rifles where intended to upgrade the M14 DMR to become a more versatile semi-automatic precision rifle that could operate side by side with the M40A5 or to stand on its own. Another influential aspect of this rifle’s birth is that it was the first precision rifle system in the USMC that incorporated a chassis. This was a huge advantage for the gunsmiths and armorers who would be building, repairing and maintaining this new rifle. For the Marines at the Precision Weapons Shop, located at MCB Quantico, the total work time involved with producing this rifle was greatly reduced. A chassis now meant that the several-day process of glass bedding an M14 DMR into its fiber-glass stock was reduced to literally half a day.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

“Ashbury Precision Ordnance has come up with very unique and functional options for the precision M1A shooter.”

When I arrived at Weapons Training Battalion in late 2006, the M39 EMR was still in the process of being developed. Nothing had been built yet, but the folks over at Marine Corps Systems Command were knee deep in bidding and sourcing the parts needed to fill the specifications the subject matter experts had written. Going through the OJT 2112 course was very much the most fun I had while in the USMC. Having just gotten back from my second combat deployment (this time to Al Qaim, Iraq), the methodical, rhythmic pace of learning a new skill was good for my life after combat. This course required us to go through a brief mathematics refresher and then a basic machinist course that really only taught us how to safely operate the equipment. I think this took about four months, and then things started getting interesting.

Going through the weapons training was where the course started to get fun. There were five firearms we had to become proficient with before receiving our certificate of completion. The M40 series sniper rifle, the MEU(SOC) M1911A1, the National Match M16 and the National Match 1911A1 were all part of our curriculum. The M14 DMR was being rotated out and replaced with the M39 EMR. Each of us had to build at least three of every kind of weapon to become familiar with them. Sometimes we were able to build more depending on how quickly others in the class were able to complete their assigned three builds. I know that when we did the MEU(SOC) portion, which took about five days, several of us were able to complete six or more pistols in the allotted time period.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

When it came to the EMR, the advantages of a chassis over a traditional fiberglass stock became clear. The rifles that were provided for modification came from Albany, Georgia. We broke them down to their barreled actions by removing the handguards and stocks. Then the students were assigned three serial numbers to start working with. The basic build of an EMR doesn’t require many aftermarket parts. Just a chassis from Sage International, an EMR barrel from Krieger and a scope base from Smith Enterprise—that’s all. Then comes the process of modifying many of the stock parts as well as the aforementioned pieces. All of this comes together in the form of the M39 EMR.

The M14 DMR and the M39 EMR are both rooted in the National Match M14 developed by the 2112 gunsmiths for the USMC Rifle Team. Heavy, match-grade barrels are the foundation for long-range precision M14s and M1As. Krieger Barrels has been supplying the USMC Rifle Team, as well as many other distinguished shooters, for years. In this case, a 22-inch, heavy-contour, 1-in-12-inch-twist, stainless steel barrel is used to stabilize projectiles up to 168 grains. The gas system is fine-tuned to provide reliable functioning as well as keeping the muzzle velocities consistent. The trigger is factory; stock triggers are very good from the manufacturer and need little attention to smooth out rough spots. The trigger pull weight is set to 3 pounds.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Adding The APO Advantage

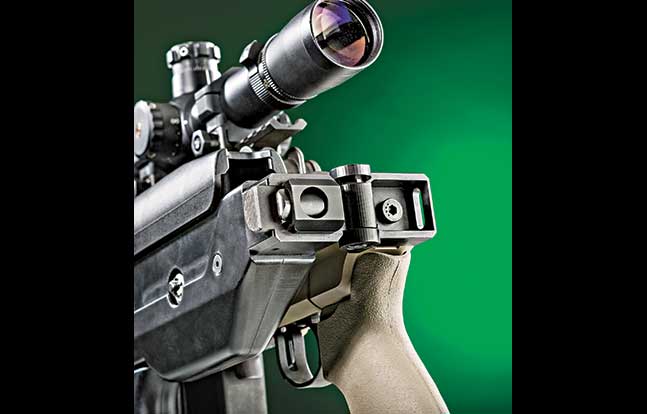

Ashbury set out to retrofit a factory Sage International EBR chassis by upgrading the retractable buttstock with its Push Button Adjustable Hybrid (PBA-H) shoulder stock. The upgrade was part of a R&D effort to provide the U.S. military a better option for the M14’s role as a precision rifle. The cheekpiece is fully adjustable for obtaining a proper cheekweld. With an adjustable length of pull, the shoulder stock can be extended up to 1.75 inches. A custom Limbsaver recoil pad soaks up most of the force that is generated by the 7.62mm NATO cartridge. Interestingly, this recoil pad is adjustable for drop (up 2.375 inches and down 1.375 inches), allowing it to be placed correctly in the shooter’s shoulder pocket. This ergonomic fit is very important when applying rapid, successive shots by keeping the recoil forces in line with the shooter’s body. There is also a butt hook that comes standard on all PBA-H shoulder stocks; however, the user may also swap this out for a monopod for stability if so desired.

But the most important feature that APO has adapted is the folding, lockable hinge. This reduces the rifle’s overall length from 44 inches to 35 inches. And with the shoulder stock folded on the opposite side of the ejection port, the weapon is still very much a useful tool when the environment becomes restrictive.

The APO M1A Hybrid built for testing uses an LRB of Long Island, Inc., receiver. The company’s M14SA action is hammer forged from SAE 8620 steel and follows the original Rock Island Arsenal USGI drawings for the military M14. This allows LRB to keep certain features of the M14 while remaining ATF compliant. Remember, the M14 rifle was equipped with a full-auto selector switch, and due to the Firearm Owners Protection Act of 1986, civilians are not allowed to own “machine guns” made after May 19, 1986.

True Performance

Shooting the APO M1A was a very pleasant experience. The optic I choose for this purpose-built rifle was a Leupold 6.5-20x50mm Mark 4 LR/T with M5 turrets in a Global Defense Initiatives (GDI) PROM mount. The Leupold Mark 4 LR/T was great for this type of semi-auto precision rifle, and it was very easy to use, with clear glass and consistent adjustments. I tested the gun’s accuracy at 100 yards.

My test ammo was a mixture of today’s more common off-the-shelf precision manufacturers, including RUAG’s Swiss P, Hornady’s TAP, Black Hills and, for good measure, the U.S. military’s own M118LR. I fired all five-shot groups from a prone position with a Long Range Accuracy (LRA) bipod and the aforementioned factory-installed monopod.

Interestingly, the Hornady 168-grain-TAP-FPD ammunition was the most consistently accurate of the test loads. I fired two groups with each type of ammo, but when the Hornady shot almost half again better than the mighty RUAG Swiss P, I felt compelled to shoot three groups in order to confirm that this was legitimate. This got me thinking: How could a non-precision load work better than the established premier loading? Muzzle velocity. And when you combine lower speeds with the slower 1-in-12-inch twist rate, you get less stability. I know what you’re thinking. Does weighing 7 grains less really matter? In a word, yes! Civilian ammo manufacturers are more focused on accuracy than speed, and most of the time this is a good way to go about making ammo for bolt guns. The RUAG and Black Hills loads are definitely performers, but in this specific application, they would not be the right choice. A slightly higher muzzle velocity would be the reason the M118LR performed marginally better than the other 175-grain loads. Military loads tend to be a bit quicker than civilian loads. But let’s not forget that even with less-than-optimal ammunition, the rifle is still capable of sub-2-MOA groups, which is the USMC’s standard for the M39 EMR.

The M14/M1A is still very relevant. This platform is a time-proven performer, and it still holds its value in today’s tactical and precision rifle market. Ashbury Precision Ordnance has come up with very unique and functional options for the precision M1A shooter.

For more information, visit ashburyprecisionordnance.com or call 434-296-8600.