It’s been over two decades since Smith & Wesson added its now-infamous internal safety lock to the side of its revolvers. If you’ve ever browsed a revolver forum, read a comment section, or even casually brought up the subject among wheelgun enthusiasts, you’ve probably heard the lock called the “Hillary Hole”—a nickname dripping with political frustration and aesthetic disdain.

What is the Smith & Wesson Revolver Lock?

Since its inception, this feature has stirred up more controversy than utility. Yet, it continues to live on in S&W’s revolver lineup.

So, what is it? How does it actually work? Does it affect how the gun feels in the hand or behaves in use? And, the question that’s probably the easiest to answer—does anyone actually use it?

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Mechanics

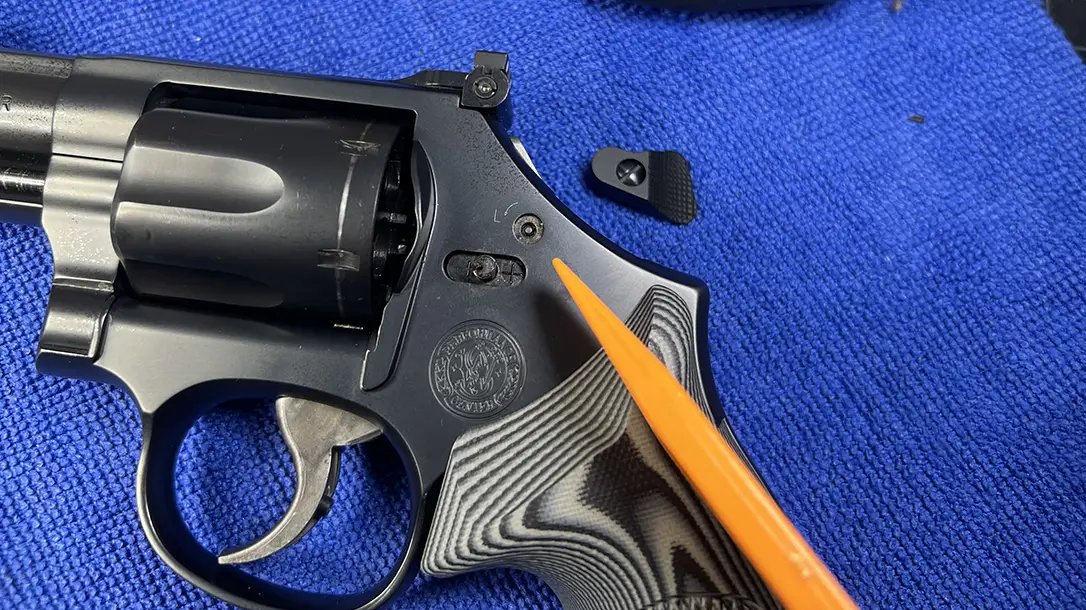

The S&W internal lock is a fairly straightforward device. Insert a small key into the left side of the revolver frame just above the cylinder release latch, give it a turn, and a cam rotates internally. That cam raises a small locking bar that engages with the hammer to disable the action entirely.

Think of it like putting a block behind the hammer. In that state, the gun cannot fire, no matter how much pressure is applied to the trigger. Likewise, the hammer will not fall. It’s dead in the hand.

Clever? Absolutely. Clunky? A little.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

But there’s no denying the mechanical execution of the design is well-thought-out. It’s also entirely passive when disengaged. When the lock is in the “off” position, it doesn’t interface with any of the moving parts in the action. It’s sitting off to the side, like a bystander.

So, when folks claim they can “feel” the lock in the trigger pull or hammer cycle, they either feel something else entirely or let their biases color their perception. Mechanically speaking, across all of the revolvers with this feature, there’s nothing to feel.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Compared to other built-in lock systems, the S&W version is robust and effective in terms of how it engages. It’s just very visible. And it’s that visibility that drives most of the distaste.

Does Anyone Use the Revolver Lock?

If we’re being honest, no. Not really.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The idea behind a built-in lock system seems practical on paper. After all, firearm safety is critical, and we all support responsible storage. But that’s just it—storage.

The vast majority of gun owners secure their firearms in safes, vaults, or locked containers. They don’t store individual guns loaded and unsecured on a nightstand with the lock engaged. It’s not a common behavior because it’s not a practical one.

If someone secures a revolver, they’re likely doing so in a way that includes all their guns in one centralized location. Not by locking each firearm independently.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Far more elegant and discreet solutions are available for those rare cases where someone wants to lock a single firearm on its own. Cable locks, trigger locks, and chamber blocks don’t permanently alter the profile or appearance of a firearm. They are also generally easier to manage if multiple people need access to the same gun.

Why the Pushback on the Internal Safety Lock?

So if it doesn’t interfere with function and no one uses it, what’s the issue? Why all the pushback?

The answer, as it often is in the firearms world, comes down to purpose and identity. Revolvers have always been the embodiment of rugged reliability. They are, by their very nature, some of the safest handguns ever made.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

With striker-fired pistols, it’s often impossible to know if there’s a round in the chamber without conducting a press check. However, revolvers wear their status on their sleeves. The brass is right there at the rear of the cylinder. You can see if it’s loaded at a glance.

Couple that with a heavy double-action trigger pull and the requirement to either cock the hammer or complete a long deliberate pull, and it becomes exceedingly difficult to have an “accidental” discharge. That mechanical redundancy is part of why revolvers have long been trusted by law enforcement and civilians alike.

So, when you take a platform already rich with mechanical safety and you bolt on a politically motivated external lock, it doesn’t sit well with the people who love these guns. It’s not that they’re worried about how the gun functions. It’s that the feature feels like a solution to a problem that didn’t exist. Worse yet, it’s one born from the optics of a political firestorm, not the mechanics of smart design.

And this gets to the root of why the lock is so disliked. It’s not a question of whether it works. It does. It’s not even about whether it breaks anything. It doesn’t. It’s about the idea that a company willingly compromised the visual and cultural identity of one of the safest firearms in existence to satisfy optics over substance.

The Final Reality

In practice, the lock changes nothing. Smith & Wesson revolvers with locks are still capable of buttery-smooth double-action pulls, crisp single-action releases, and world-class accuracy. They’re still used in competition, hunting, defense, and recreation.

If you want to build a speed rig or tune your revolver for precision shooting, you absolutely can. The lock does not get in your way—unless, of course, you decide to remove it. Which, for many enthusiasts, is an easy Saturday project. Though officially speaking, tampering with or altering a safety device is not recommended.

So, what are we left with? A feature that nobody uses, that doesn’t get in the way, but that still feels out of place. Aesthetically, it’s a blemish. Philosophically, it’s unnecessary. Functionally, it’s clever. And politically, it’s a scar some folks never wanted in the first place.

Will Smith & Wesson ever get rid of it? It’s hard to say. They’ve stood by it this long, and despite years of customer feedback, it’s still there on most models. Perhaps they feel it’s a low-cost insurance policy, or maybe it’s just too embedded in their production flow to undo. But for now, it’s simply part of the deal.

Shoot Safe.