Today, we are spoiled for options when it comes to concealed carry handguns. You can pick revolvers and semi-autos in any number of calibers, capacities, and frame configurations. But year after year, new handguns seem to be refinements of what came before. Today, we dive into the history of concealed carry and spend a day with the Smith & Wesson New Departure.

The Smith & Wesson New Departure

At the turn of the 20th century, there were no permit schemes, but small handguns and tight lips. The problem then was a political environment hostile to carrying firearms. This was juxtaposed with a gun industry that was changing at a rate never seen before or since.

In 1860, most handguns were black powder muzzleloaders. A mere generation later, we had the first semi-auto pistols and smokeless ammo. A laundry list of handguns rose, fell, and stuck around, ranging from single-shot derringers to the latest automatics that you could buy from a print catalog.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

But perhaps the most iconic handgun of the type was the Smith & Wesson New Departure. It will forever be remembered as the Smith & Wesson Lemon Squeezer.

A New Departure?

As the name would suggest, Smith & Wesson coined it to separate its old generation of single-action revolvers that defined the Old West from a new generation of handguns designed to tame the urban frontier.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Smith & Wesson was best known for its No. 3 break-action .44-caliber revolvers, as well as its tiny No. 1 and No. 2 tip-up revolvers, chambered in .22 and .32 rimfire. Later, the lineup was redesigned for the .32 S&W and .38 S&W centerfire cartridges. Likewise, it was given a stronger break-action just like the No. 3.

These new No. 2 revolvers debuted in 1878 and were single-action, which required thumbing the hammer before firing each shot. The new No. 2 sold well. But as revolvers like the British Bulldog and Colt Lightning made inroads, the need for a faster double-action revolver emerged. The first double-action No. 2 revolvers debuted in 1880.

The Smith & Wesson New Departure arrived seven years later. This model, sometimes referred to as a Safety Hammerless, was double-action. As a result, it could be fired as quickly as the user could pull the trigger. The hammer spur found on other pocket handguns of the time, which posed a snag risk while drawing, was eliminated.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Safety Hammerless does have a hammer, but it is enclosed within the frame. Correspondingly, the New Departure also featured a grip safety. This prevented the revolver from firing unless the grip safety was depressed with the firing grip and the trigger pulled.

It also made the New Departure drop safe in an era where most handguns still needed to be kept with an empty chamber under the hammer for safety. The distinctive safety also earned the revolver the moniker “lemon squeezer.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

A Long Run for the Wheelgun

The New Departure was produced in two models: a small-frame .32 S&W model and a larger-framed version in .38 S&W. Both were five-shot top-break revolvers that remained aesthetically unchanged throughout their production run.

The cylinder release latch was moved, and the addition of two locking lugs over a single lug in the early models marked the steady transition of the model from black powder to smokeless ammunition. There were four sub-models in the run. The first two iterations were all made before 1909 and were proofed with black powder.

The Smith & Wesson Lemon Squeezer has a long run stretching from 1887 until 1940, with over 260,000 units sold. During that time, there were a few design changes that paled in comparison to the changes in handgun technology going on around a model that seemed suspended in time, not long after its release.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

A New Departure for the New Departure

Copycat designs like the Iver Johnson Safety Automatic were cheaper, carefully marketed, and fit the bill for most people. Only two years after the Safety Hammerless, Colt debuted its first swing-out cylinder revolver. As a result, Smith & Wesson had to play catch-up.

These stronger, solid-framed handguns could handle longer and more powerful cartridges at the time of transition to cleaner and more powerful smokeless ammunition. By the 20th century, Smith & Wesson had established the foundation for its modern service and pocket revolvers. But little break-tops like the New Departure continued to sell well for those looking for an inexpensive handgun in an adequate caliber.

The New Departure was discontinued in 1940, but the idea of the hammerless revolver was only getting started. Shortly after launching the Chief’s Special in .38 Special, Smith & Wesson launched the Centennial in 1952. It marked Smith & Wesson’s 100th anniversary and came with a grip safety and a shrouded hammer for deep carry.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The grip safety would not survive in lieu of hammer block safeties. However, the Centennial design went on to influence all double-action-only revolvers made by Smith & Wesson and countless other makers.

Disassembling the S&W Lemon Squeezer

Like a modern Smith & Wesson revolver, the New Departure features a side plate that must be dismounted for servicing. However, how it dismounts differs and it can lead to frustration and boogered screws.

The first step is to remove the grips followed by a small set screw in the side plate. There is a larger threaded cap that looks like a screw in the center of the side plate. It threads into the fixed hub that the hammer rides on. If you try to unscrew this cap, it will continue to turn even when it backs out of its recess.

Don’t try to get it off with a screwdriver. Instead, pop the side plate out of its mortise with a non-marring punch. The cap will come off with it.

A Lemon Squeezer in the Hand

With its large trigger guard and humped appearance, the Smith & Wesson New Departure was that occasional movie gun that plays a bit part that I could not quite forget.

Concealed carry through the ages is something of a pursuit of mine. I first became acquainted with top-break pocket pistols in my historical research on anarchist movements at the turn of the century. The Iver Johnson Safety Automatic came up constantly. So, I got to wondering what Smith & Wesson was doing at the time and had to try their alternative.

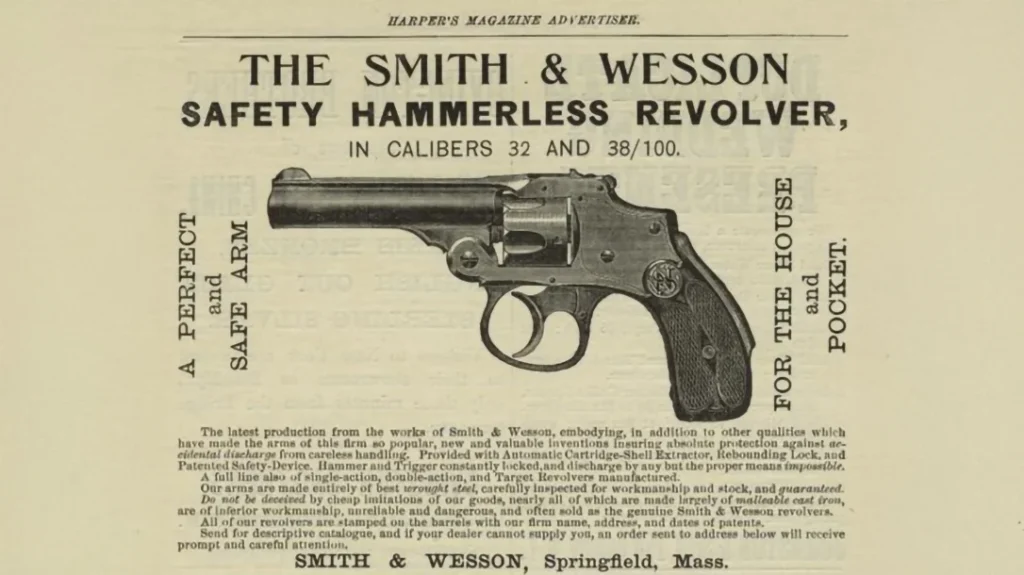

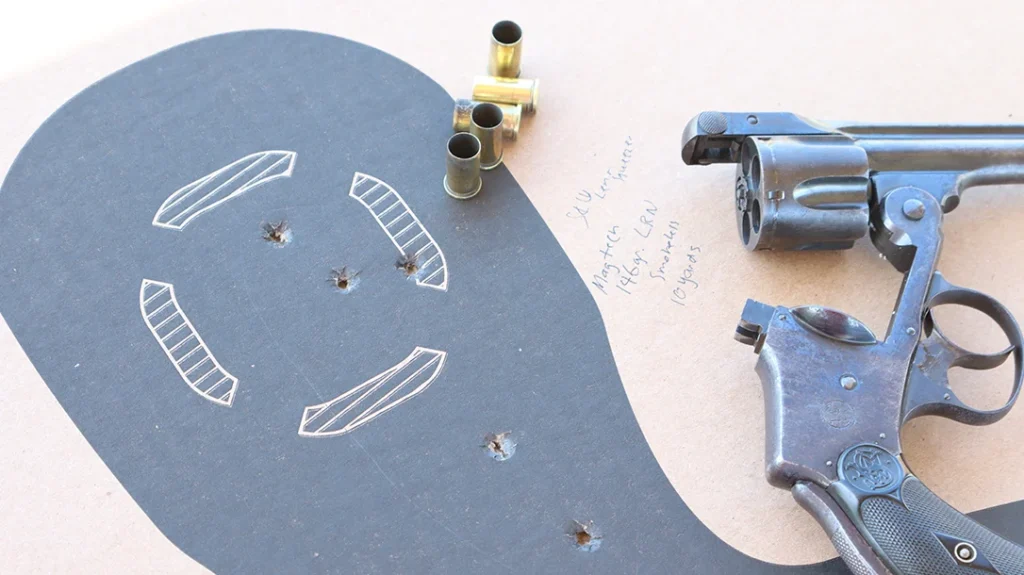

The Lemon Squeezer I stumbled upon is a 2nd Model, which was made between 1902 and 1909. It features a three-inch barrel and is chambered in .38 S&W. Although much of the original bluing has faded to a patina, the revolver remains mechanically perfect.

The hard rubber grips are also completely intact, unlike those that commonly crack with age and handling. The revolver looked to be a shooter, but I had a choice between ammunition: smokeless or black powder.

Black Powder or Smokeless?

The .38 Smith & Wesson cartridge, like the Smith & Wesson New Departure, transitioned from black powder to smokeless. Some shooters of these older black powder-proofed models get away with modern smokeless loads. This is because manufacturers download the ammunition with older, weaker break-top revolvers in mind.

The problem comes with high-pressure curves over continued use. You can load modern .38 S&W down to lower black powder pressures. However, smokeless does not burn up instantly like black powder. For black powder-rated guns, it is really best to stick to black powder cartridges.

Buffalo Arms makes runs of .38 black powder loads, but it is mostly a handloader’s project. I decided to take a few boxes of Magtech 146-grain lead round-nosed .38 Smith & Wesson ammunition and reload them with black powder. I also re-lubed the bullets with my favorite black powder lube: half olive oil and half beeswax.

For the sake of being thorough, I left a handful of the factory ammunition loaded as is.

Revolver Ergonomics

If you are used to short resets and suppressor-height sights, the little Safety Hammerless may be a letdown. But for what little it has by modern standards, it is surprisingly shootable.

Loading the Lemon Squeezer is simple. Draw the cylinder latch upward with your off-hand fingers and tip the barrel forward. The ejector star will rise and, at the end of its travel, fall flush with the cylinder. From there, you can load in your five rounds of ammunition and close the revolver.

This is a double-action-only revolver, among the first of its kind. So, all you have to do to fire is get a grip and press the trigger all the way through.

The grip on the Safety Hammerless is small, and there is no tactile feedback to indicate whether you have depressed the grip safety or not. Surprisingly, I am not wanting for extra grip, even with my large hands. The reach for the trigger is just right. In addition, the slight recoil of the .38 S&W cartridge means that the slick grips don’t move in the hand from shot to shot.

The sights are perhaps the most surprising aspect of the Lemon Squeezer. The front sight consists of a pinned front half-moon and a narrow rear notch forward of the frame latch. From a cursory glance, it looks like there is no rear sight at all until you find the nub that poses for a notch.

Despite their small size, their thin profile makes for a fine sight picture if you are going for groups. But those with poorer eyesight might not be able to pick up the rear sight at all. In any case, the Lemon Squeezer was not made for taking potshots across the canyon.

Shooting Impressions

I shot the Smith & Wesson Safety Hammerless out to a distance of ten yards with both my black powder reloads and a handful of Magtech 146-grain smokeless rounds. From that distance, I could reliably put five rounds into the size of my hand with either load.

Recoil was mild, and noise amounted to a pop rather than a crack. But the black powder loads felt just a little more authoritative. This is backed up when I fired five rounds of each ammunition across my Caldwell chronograph.

From ten feet away, the black powder .38 S&W rounds were clocking in at an average velocity of 652 feet per second. The Magtech load came in at only 528 feet per second! Modern .38 S&W does not exactly inspire confidence. However, properly loaded ammunition is on par with modern .380 ACP loads in terms of energy.

The shooting experience was pleasant all around. Loading, shooting, and most importantly, ejecting the empty cases, never gets old.

The only part to get used to, aside from the low sights, is the trigger pull. In terms of weight, it breaks smoothly at ten pounds. Correspondingly, it resets all the way out like any other Smith & Wesson hammerless revolver.

The lockup can be readily felt and heard in the trigger at the end of its travel. So, you will know when the trigger is about to break. That is a definite aid in shooting if you are not used to double-action-only setups.

In the end, I was left with a box of empty cases and a newfound respect for what constituted concealed carry at the turn of the last century.

The New Departure in the New Century

The Smith & Wesson New Departure has more than earned its place in concealed carry history. Revolutionary for its time, it ultimately led to a dead end. However, it lingered on well beyond its prime and experienced an unexpected revival.

It became the inspiration for the modern hammerless revolver that thrives in the era of the semi-auto and is a surprisingly affordable piece of history. Some are in rough cosmetic shape. However, they are often more mechanically sound than one might think, given the large number that were purchased and stored for a time of need that never came.

Often overlooked for their appearance and mistaken for cheaper knock-offs, the New Departure can be had for a fair shake. Whether you are a Smith & Wesson collector, history buff, or need a beater gun for the trap line, the old Lemon Squeezer still has plenty to offer.

Smith & Wesson New Departure Specs:

| Caliber | .38 S&W |

| Capacity | 5 |

| Barrel Length | 3 inches |

| Overall Length | 7.75 inches |

| Width | 1.3 inches |

| Weight | 20.6 oz. (loaded) |