May 28, 1862

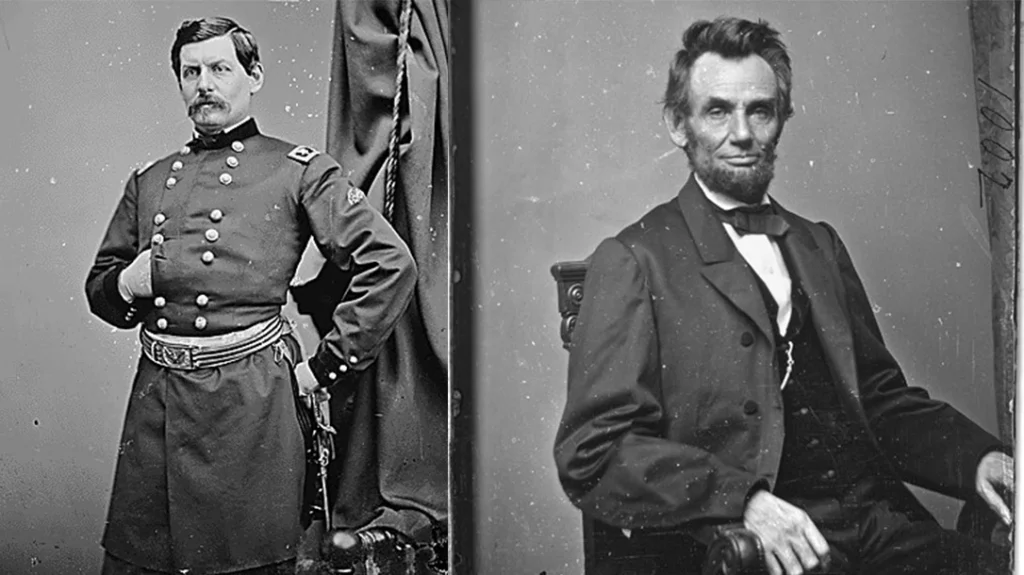

Abraham Lincoln was concerned. He wasn’t frightened, but he was concerned. Union General George B. McClellan was poised before Richmond with 90,000 men, aiming to end the American Civil War less than a year after the First Battle of Bull Run.

But the Confederates weren’t giving up easily. President Lincoln had reports that General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s small army now controlled the Potomac River crossings at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, and could possibly threaten Washington DC.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Despite outnumbering the Confederates by more than 30,000 men, McClellan was clamoring for reinforcements. Lincoln had General Irvin McDowell’s 40,000 men a short distance away near Fredericksburg. He also counted on two smaller commands in Maryland and western Virginia. Stonewall Jackson was positioned to threaten the supply lines of all three of these fighting groups. The Union’s opportunity to take Richmond and possibly end the Civil War hung in the balance. What to do?

The Confederate Problem

McClellan proposed moving the Union Army of the Potomac by sea to the peninsula between Virginia’s York and James Rivers in order to attack Richmond. It was a sound idea. The US Navy owned the waves, and the move bypassed the defensible river lines between Washington DC and the Southern capital. Confederate commander General Joseph E. Johnston had never seen a position from which he was unwilling to retreat, so McClellan moved rapidly up the peninsula toward the enemy city after landing in mid-March of 1862.

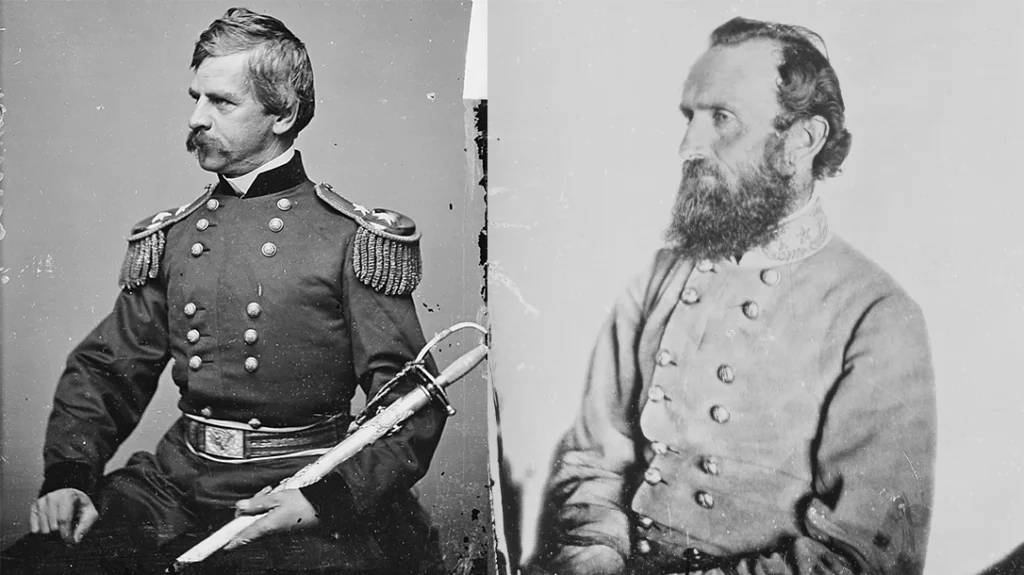

McClellan positioned Union General Nathaniel P. Banks’ 23,000 men at Manassas Junction, a major rail crossing. Some of these men were also sent to the lower Shenandoah Valley to support McClellan’s right flank (along with McDowell south of Washington).

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

McDowell was to eventually march south and threaten Richmond’s left flank. McClellan hadn’t planned to leave McDowell behind at all, but Lincoln overruled him, wanting more security for the Union capital.

Having only 57,000 troops to oppose McClellan’s 90,000 (not counting McDowell and Banks’ men), Johnston looked for an alternative. Stonewall Jackson’s command in the Shenandoah was the only force positioned to influence events at Richmond. As Federal troops landed on the peninsula, Johnston ordered Jackson to prevent Banks and McDowell from joining McClellan.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s military Chief of Staff, General Robert E. Lee, concurred and urged Jackson to move.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Jackson’s Situation in the Valley

A deep dive into Jackson’s brilliant Shenandoah Valley Campaign would make this article quite long. Instead, let’s focus on how Jackson maneuvered to accomplish the mission that Johnston and Lee gave him. We’ll also look at its strategic fallout.

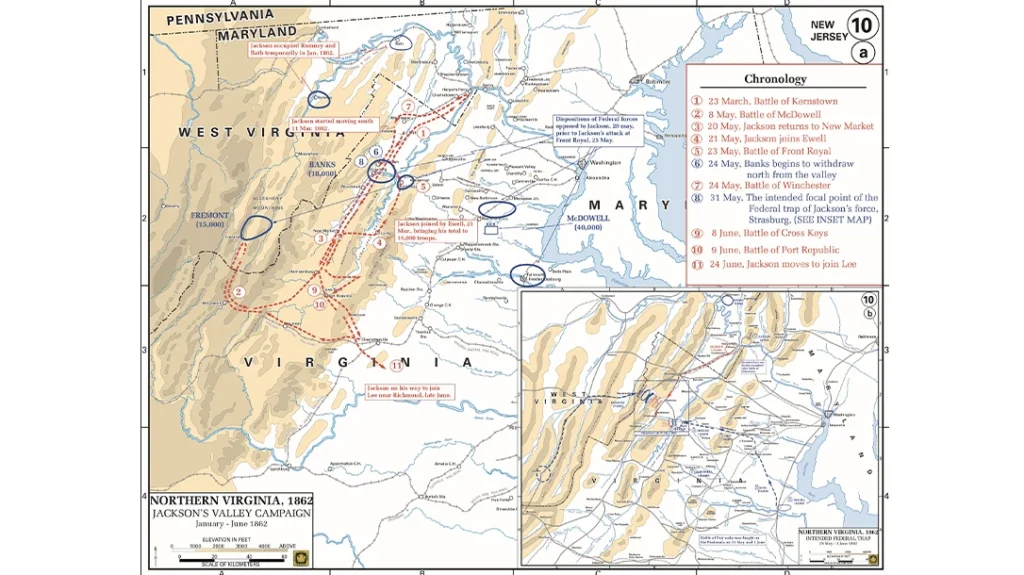

Jackson began the campaign with only 4,600 men. But he had access to General Richard Ewell’s 8,000 men just east of the Valley and General Edward Johnson’s 2,800-man force guarding the western approaches. Banks opposed him in the Valley, while Union General John C. Fremont was moving east with 15,000 men through current-day West Virginia, opposite Johnson.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

First Battle Of Kernstown

Banks had moved south to Winchester, VA on March 11, forcing Jackson’s retreat up the valley (south). Seeing Jackson’s small numbers, Banks soon left General James Shields’ division at Kernstown, just south of Winchester. Banks then joined McClellan, who was just embarking for the peninsula.

Stonewall Jackson subjected his forces to one of his infamously grueling marches in order to immediately move to attack Shields at Kernstown on March 23. Jackson had received faulty from Confederate loyalists intelligence that Shields was also leaving, just like Banks.

However, Shields’ entire division was present at Kernstown. Union forces repelled the advanced and Jackson’s army suffered a defeat. In a twist of irony, Jackson’s aggressiveness convinced Shields, Banks and Lincoln that Jackson’s numbers were bigger than they truly were.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Why else would he attack a force twice his size–and so quickly?

Jackson’s moves with a few thousand men summarily influenced the movements of more than 70,000 Union troops. Banks turned around. Lincoln ordered McDowell to remain in place to protect Manassas Junction. On top of that, Lincoln also dispatched another 7,000 men to reinforce Fremont’s army. The First Battle of Kernstown was a tactical defeat for Jackson, but a strategic victory for the Confederacy. It was Stonewall Jackson’s moves in the Shenandoah Valley that made him the most famous Confederate general, after Robert E. Lee.

Stonewall’s Sleight of Hand

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Jackson withdrew up the Shenandoah Valley after Kernstown and spent time recruiting and training men to bolster his force to 6,000 strong. Banks cautiously followed. Jackson ensconced himself in the Blue Ridge’s Swift Run Gap, which allowed him to watch Banks and protect his supply base at Staunton. From this position, Jackson could also move east to support Richmond if necessary.

Lee received word on April 21 that McDowell was marching south. His advance guard was already on the Rappahannock River opposite Fredericksburg, only 60 miles from Richmond. McDowell was clearly moving to link up with McClellan and threaten Richmond from the north.

The only Confederate unit in the Union Army’s path was a 2,500 man brigade. With such small numbers, it had no chance to slow down Union forces. Lee urged Jackson to move swiftly to counter McDowell.

Jackson marched from Swift Run Gap, through the village of Port Republic, to Brown’s Gap. There, he exited the Shenandoah Valley to the east. He purposely moved in full view of Banks’s scouts. Banks concluded that Jackson was moving to Richmond. So reported that the Confederates were leaving the valley “permanently.” Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered Banks to move James Shields’ Second Division and join McDowell in Fredericksburg. This left Banks with a single division of 14,000 men.

Once clear of the Valley, Jackson marched to Meechum’s Station. Here Jackson arranged rail transport–not to Richmond–but back to Staunton. Jackson was able to quickly maneuver back into the Shenandoah while Banks was looking elsewhere.

Maneuvering Through The Valley

Ewell’s 8,000 men moved into Swift Run Gap from the east. Jackson then joined with Johnson, attacking and driving back Fremont’s advance guard at McDowell, Virginia.

Jackson, now reinforced by Johnson and Ewell, attacked Banks’outnumbered division north of Staunton. Banks fled headlong down the valley for about 80 miles. Banks did not stop until he reached Strasburg. Jackson’s quick countermarch had cleared the upper portion of the Shenandoah Valley and set the stage to immobilize General McDowell.

Flank March to Winchester

Jackson’s cavalry pursued Banks hard, thus covering Jackson’s next moves. Banks dug in before Strasburg, convinced that Jackson would attack his army there. He posted 1,000 men to protect the railroad junction in Front Royal, VA, 10 miles to the east. The Confederate cavalry pressure maintained this illusion. But Jackson had other plans.

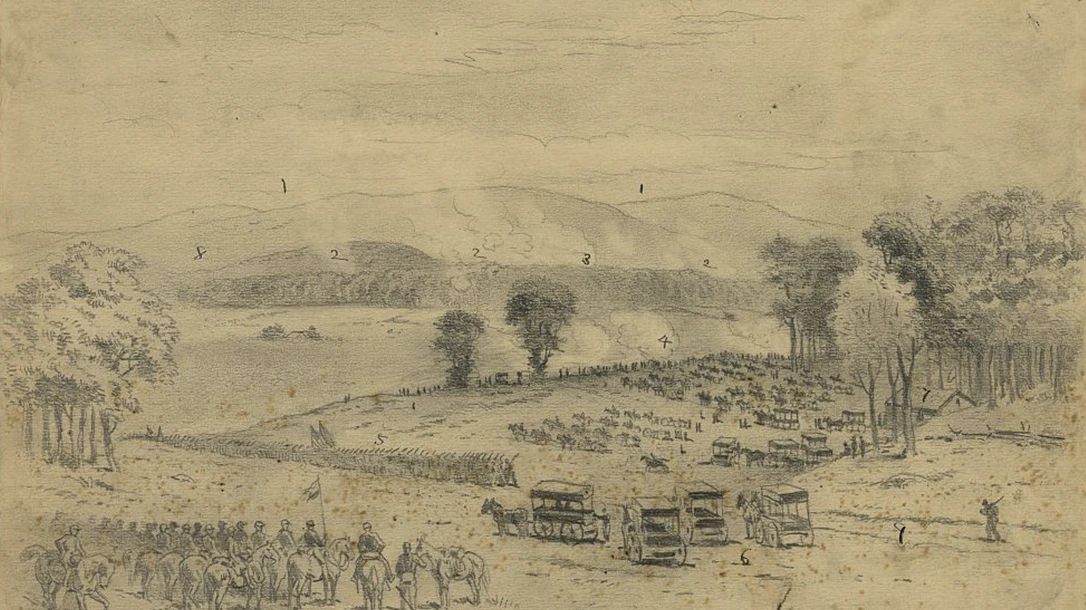

Massanutten Mountain splits the Great Valley of Virginia, with the Shenandoah to the west and the smaller Luray Valley to the east. The only pass through Massanutten is the Luray Gap. It’s located just east of New Market, 45 miles north of Staunton. Jackson sent Ewell north through the Luray Valley, while he pushed hard up the Valley Pike, seemingly pursuing Banks.

But Jackson turned east at New Market, joining Ewell and proceeding down the Luray Valley to where Front Royal sat at its mouth. Massanutten mountain’s terrain and layout blocked any prying eyes. With Confederate cavalry still feinting at Strasburg, Jackson’s force descended on Front Royal like a thunderclap. It captured 700 Union soldiers and put the rest to flight.

Afterward, Jackson turned west toward Winchester, firmly on Banks’s left flank. A quick march may have bagged Banks’ entire command, but Jackson had to be mindful of Shields and McDowell to the east.

Consequences Of Front Royal & Winchester

Banks’ reaction caused his division to run for Winchester hastily. This resulted in Banks’ force losing most of its service and supply wagons while Jackson pursued. Banks’ men fought to hold Winchester, but Jackson took the town on May 25. As Federal troops retreated, they were subject to gunfire and hurled objects from Winchester residents, primarily women.

The day before, Lincoln recalled McDowell. General McDowell crossed the Rappahannock river toward Richmond. But President Lincoln clearly saw that Front Royal’s fall allowed Jackson to threaten Manassas Junction–and McDowell’s all-important supply lines.

Jackson’s 17,000 men had just halted McDowell for the second time, while putting Banks to flight.

Pursuit to the Potomac

Robert E. Lee wrote to Jackson on May 16, prior to Front Royal, ordering him to drive Banks north and threaten the Potomac River crossings. Those crossings were vital supply links to McDowell’s force and other points south. Even if they weren’t cut, threatening these supply lines would hold McDowell at Fredericksburg and perhaps even force his withdrawal.

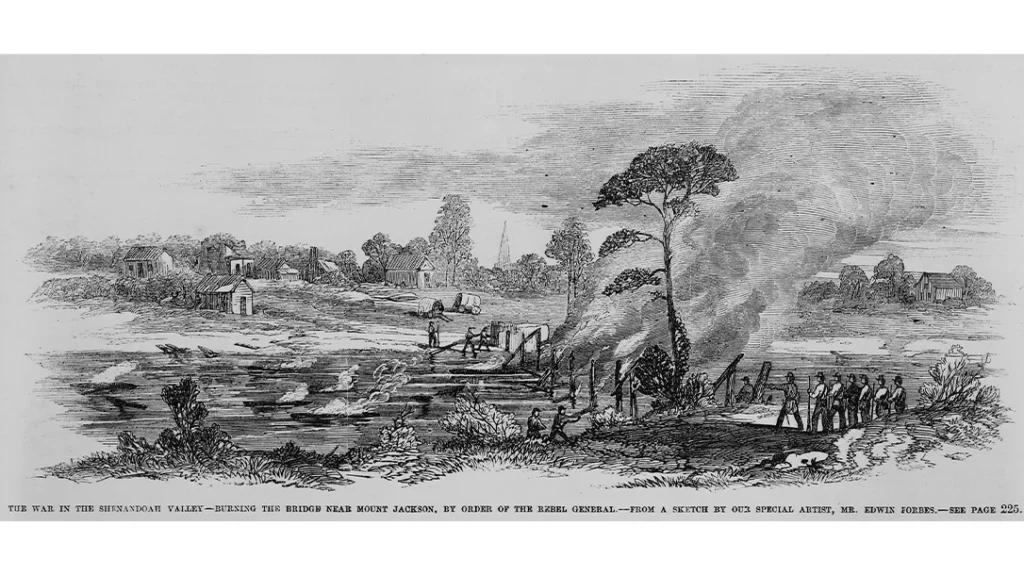

After securing Winchester, Jackson’s forces marched north on the heels of Banks’ division. Banks crossed the Potomac at Harper’s Ferry. Jackson’s advance units arrived on May 28.

On May 30, Jackson received word from Johnston and Lee instructing him to threaten Baltimore or other Northern cities, “if practicable.” Jackson was willing, but he needed more men and had other problems.

Lincoln Tries To Counter-Maneuver The Foot Cavalry

Lincoln’s May 24 order to McDowell had included instructions to send Shields’ 9,000 men west to trap Jackson in the lower Valley. He also ordered Fremont’s force to enter the Shenandoah and cut off Jackson at Harrisonburg. The President not only wanted to protect Manassas Junction, but he also wanted to bag Jackson. Confederate scouts sent word up as soon as Shields turned west. Lincoln’s plan was quite technical and required coordinated and precise movements in order to work. The hope was to trap Jackson’s army in Strasburg. Pulling it off in the context of 19th century warfare would have been a major feat. The plan left no margins for either Banks or Fremont.

Jackson was infamous for subjecting his men to grueling marches. This earned his soldiers the name “Jackson’s Foot Cavalry.” True to the name, Jackson’s army marched nearly twice as far as Shields’ in the same time. This allowed the Confederate force to escape past Strasburg and thwart Lincoln’s counter-maneuver.

Unfortunately for the Union, Fremont had to contend with not only extremely difficult road conditions but also a large swat of territory that needed coverage on the western portion of the Shenandoah. So instead of moving east toward Harrisonburg, Fremont’s army moved north towards Strasburg in order to connect Shields’ forces. The Federal counter-maneuver ultimately failed.

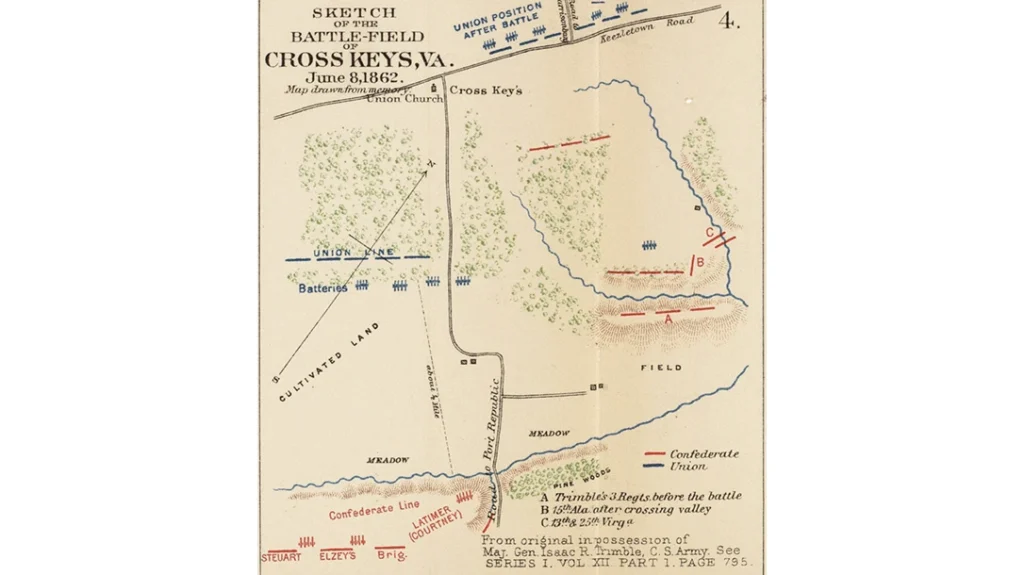

Cross Keys & Port Republic

Jackson’s Valley campaign ultimately culminated by two decisive victories at Cross Keys and Port Republic the day after. Though costly for Jackson’s army, the result of these Confederate victories caused the Union armies to retreat. This also allowed Jackson to freely move and rally with General Lee’s forces near Richmond prior to the Seven Days Battles. In turn, the Seven Days Battles were the culmination of McClellan’s original Peninsula campaign referenced above.

Strategic Implications

Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign lasted from his March 23 attack on Kernstown to the final repulse of Shields and Fremont in early June at Cross Keys and Port Republic. He never had more than 17,000 men at his disposal. Jackson’s decisive maneuvers prevented his adversaries from concentrating against his small army and overwhelming it, while he threw his full weight on their flanks.

Jackson’s goal was to prevent 63,000 Union troops from joining McClellan on the Peninsula campaign because of the threat it posed to the Confederate capital. He was also tasked with protecting Richmond’s northern approaches.

He accomplished that mission with aplomb. He also redirected Fremont’s 22,000 men, meaning Lincoln could not replace Banks with Fremont. In all, his 17,000 ran rings around 85,000 Union troops by marching 646 miles in 48 days. This tied up three Union armies and denied them to McClellan’a main effort thus protecting Richmond.

From an abstract military perspective, Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley campaign was brilliant. Modern military officers still study it for a reason. In terms of human suffering, Jackson’s victories meant death and misery for hundreds of thousands of people. Certainly one could argue that the war’s outcome would have had to be more decisive to destroy Southern institutions–as Willian Tecumseh Sherman did during the later part of the war.

Stonewall Jackson conducted his campaign in the finest traditions of Napoleon, Frederick the Great, and Sun Tzu, though he’d never read the latter. Finding an action in which 17,000 men so impacted the course of a major war is difficult indeed. It’s why Jackson is often ranked among America’s greatest commanders.