“Come along, boys, and listen to my tale; I’ll tell you of my troubles on the old Chisholm trail.” Those words start the poem “The Old Chisholm Trail.” While the author is unknown, the work is a beautiful piece of prose. It celebrates the ups and downs of punching herds of cattle up the historic route that many have long forgotten. Let’s take a trip down the Chisholm Trail.

The Chisholm Trail – The Cattle Highway

The Chisholm Trail is known by many as an important route for cattle drives during America’s wilder days. But many people aren’t unaware of how important its development and use were for both large Texas ranchers and the more civilized citizens of the Eastern states.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I grew up near a small Oklahoma town (Tuttle) where the old Chisholm Trail ran right across Main Street. It was not far from the high school football stadium. Consequently, most of our grade school class field trips involved learning about the historic trail. We saw the historical marker every time we dragged Main Street. Trust me, was more times than we could even think about counting. Eventually, we didn’t even notice it anymore. It was just another sign alongside the road on the way to school or wherever our travels took us.

Imagine my surprise when I grew older and realized that many people weren’t even aware that the Chisholm Trail existed. They might not have even heard of it if. They didn’t happen to run across one of the historical markers that dot roadsides along the old path!

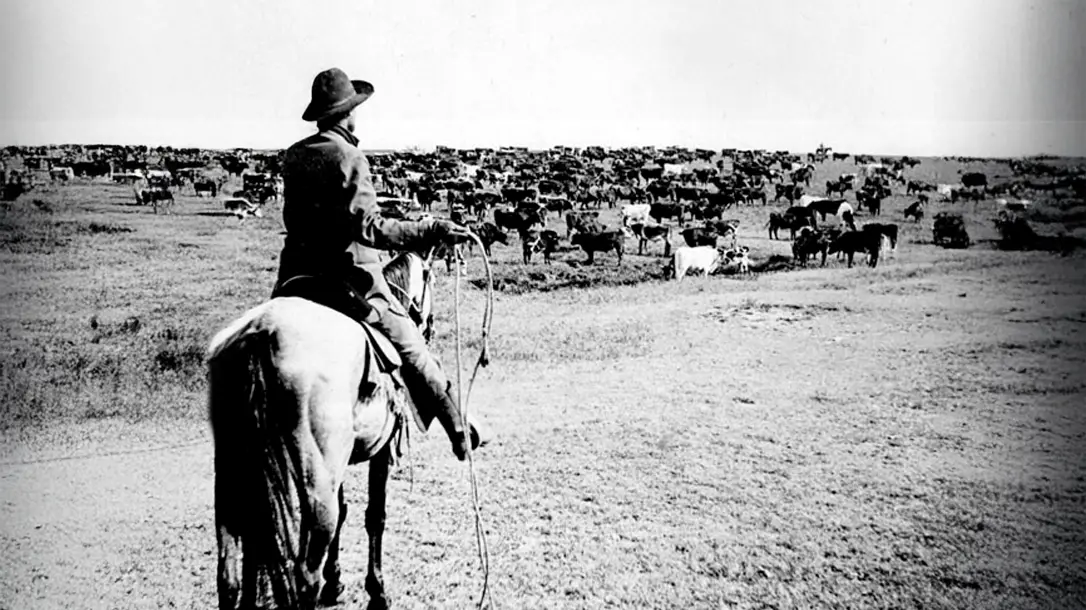

With that in mind, let’s take a look at this historic route. It was used in the post-Civil War era to drive beef cattle from Texas to the Kansas railheads. Where they were shipped back East to feed the throngs of people who couldn’t produce meat for themselves.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In The Beginning

Before 1867, ranchers in Texas raised their longhorn cattle but largely didn’t have a ready market for them. People back East, of course, needed the beef. But there wasn’t a logical way to get cattle from Texas to the East Coast.

That is until 1867, when the railroad reached Kansas. Texas ranchers saw their opportunity to send beef east on trains and open up a great new market. Unfortunately, more than 1,000 miles of rugged country separated points in southern Texas from the railhead in Kansas.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Once the railroad reached Abilene, Kansas, and pens were built to hold cattle before shipping, Texas ranchers began trying to take advantage of the new market. And for Texas cowhands, the opportunity to participate in these long-distance drives of sometimes thousands of cattle at a time offered both great adventure and great peril.

According to the Texas State Historical Society:

“The first herd to follow the future Chisholm Trail to Abilene belonged to O.W. Wheeler and his partners, who in 1867 bought 2,400 steers in San Antonio. They planned to winter them on the plains, then trail them to California. At the North Canadian River in Indian Territory (current day Oklahoma), they saw wagon tracks and followed them. The tracks were made by Scot-Cherokee Jesse Chisholm, who, in 1864, began hauling trade goods to Indian camps about 220 miles south of his post near modern Wichita. At first, the route was merely referred to as the Trail, the Kansas Trail, the Abilene Trail, or McCoy’s Trail. Though it was originally applied only to the trail north of the Red River, Texas cowmen soon gave Chisholm’s name to the entire trail from the Rio Grande to central Kansas.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

From 1886 to 1884, the Chisholm Trail was a hotbed of activity as ranchers took advantage of the market opportunity, and cowhands went along for work and adventure. Herds traveled about 10 to 25 miles a day, and outfits averaged about 10 cowboys for every 2,500 steers. During that period, some 6 million cattle and an equal number of mustangs were driven up the trail, making it what many historians say was the most significant livestock migration in history.

The Chisholm Trail was finally closed by widespread use of barbed wire and an 1885 Kansas quarantine law. By 1884, its last year, it was open only as far as Caldwell, in southern Kansas.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Chisholm Trail –Life On The Trail

Of course, life on the Chisholm Trail was fraught with disaster—not the least of which was a number of sometimes large rivers that often were high after heavy rains. In fact, the Red River could rise as much as 25 feet in a day after substantial rainfall. Such rivers could cause the loss of both cattle and cowboys, as chronicled at history.net:

“Todd [the trail boss] called one of his hands, Jim Foster, a cowboy young enough to be ‘generous with his life as with everything else,’ as Western chronicler J. Frank Dobie later said. The lead steers were driven into the river but, about halfway across, began swimming in a circle. The jam of milling cattle had to be broken before the animals at the center were pushed under and drowned.

Foster stripped to his union suit and drove his horse into the river. He climbed off the horse and onto the backs of the Longhorns, walking across the herd as if it were a logjam. Straddling one of the biggest steers in the herd, he forced it to swim to the far bank. The rest of the herd followed, and Foster spent the remainder of the day–from 9 a.m. to dusk–keeping the herd together on the northern bank, soaked to the skin in his underwear until the other cowboys got across the river to relieve him. For this notable piece of work, Foster received the princely sum of one dollar, a standard day’s wage on the Chisholm Trail in 1871.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Trail Dangers

Of course, swollen rivers weren’t the only dangers on the Chisholm Trail. The areas of the trail in Texas and southern Oklahoma consist nearly entirely of plants and animals that stab, scratch, poke, bite, or otherwise cause injury. Getting thrown from a half-trained bronc used as a cowpony wasn’t uncommon. And, of course, there were outlaws looking to cut a few heads of beef out of the herds or steal the herd entirely. The various wild animals that could cause a stampede in a heartbeat, and not-so-civilized Indians who still didn’t appreciate the encroachment of thousands of cattle on their prime hunting grounds.

And then there was the poor food that could be encountered in camp each night. Especially for those trail outfits not blessed with a good cook or who lost their cook somewhere along the way. For proof, look no further than the Jesse Chisholm Grave Site. About six miles north of Geary, Oklahoma, in rural Blaine County. I drive past the historical marker every time I go to and from deer camp. I usually shake my head at the trail founder’s bad luck. After several successful trips up and down the northern portion of the trail, Chisholm died of food poisoning on March 4, 1868, as the historical marker says, “after eating bear meat cooked in a copper kettle.”

Learning More

Because of the vast length of the trail and its close proximity to many small towns, current cities from south to north claim the trail as their own. Consequently, there are nearly a half dozen different museums in Texas, Kansas and Oklahoma honoring the old trail.

One of the biggest is the Chisholm Trail Heritage Center in Duncan, Oklahoma. There, you can find not only various exhibits portraying the trail. But if you want you can rope a steer, feel the adrenalin rush of a stampede and meet many fascinating characters who frequented the trail.

If you ever have the opportunity to visit there, be sure to see the life-size bronze aptly named “On The Chisholm Trail.” Standing nearly 15 feet high atop the immense base. It stretched about 35 feet across the horizon, this majestic work of art is truly a monument to the American cowboy

There are other facilities that feature an interesting history of the trail, along with various artifacts of the trail’s history. These include the Chisholm Trail Museum in Kingfisher, Oklahoma; Chisholm Trail Outdoor Museum in Cleburne, Texas; Chisholm Trail Heritage Museum in Cuero, Texas; and the Chisholm Trail Museum in Wellington, Kansas. All have something special to offer. A trip up the historical trail visiting each one of these locations would likely be a Western historian’s dream vacation.

The Chisholm Trail – Life In A Bygone Era

The era when herds went up the Chisholm trail was a simpler time. But they were far from easy on the tough men trying to make a living driving cantankerous cattle 1,000-plus miles through rugged country. These were Old West characters at their best, some well-known in history. Some only known by their compadres around the campfire at night.

I’ll leave you with the poem that I briefly quoted to start this story. “The Old Chisholm Trail,” can give readers with imagination a little bit of feel for what life was like on a cattle drive on the trail.

“The Old Chisholm Trail”

“Come along, boys, and listen to my tale; I’ll tell you of my troubles on the old Chisholm Trail.

“I started up the trail on October 23; I started up the trail with the 2-U herd.

“O a ten-dollar hoss and a forty-dollar saddle, and I’m goin’ to punch in Texas cattle.

“I woke up one morning on the old Chisholm Trail, rope in my hand and a cow by the tail.

“Stray in the herd, and the boss said to kill it, so I shot him in the rump with the handle of the skillet.

“My hoss throwed me off at the creek called Mud, my hoss throwed me off round the 2-U herd.

“Last time I saw him, he was going ‘cross the level, a-kicking up his heels and a-running like the devil.

“It’s cloudy in the west, a-looking like rain, and my darned old slicker’s in the wagon again.

“The wind commenced to blow, and the rain began to fall, hit looked, by grab, like we were goin’ to lose ’em all.

“I jumped in the saddle, grabbed hold of the horn, best-darned cowpuncher that ever was born;

“I popped my foot in the stirrup and gave a little yell; the tail cattle broke, and the leaders went as well.

“Feet in the stirrups and seat in the saddle, I hung and rattled with them longhorn cattle.

“I don’t give a darn if they never do stop; I’ll ride as long as an eight-day clock.

“We rounded ’em up and put ’em on the cars, and that was the last of the old Two Bars.

“Goin’ to the boss to get my money, goin’ back south to see my honey.

“With my hand on the horn and my seat in the sky, I’ll quit herding cows in the sweet by-and-by.”